The Final Report to Parliament on the Review of S-3: December 2020

Table of contents

- Message from the Minister

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Covid-19

- Background on Sex-Based Inequities in the Indian Act

- Objective 1: Reviewing the Elimination of Sex-Based Inequities

- Objective 2: Review of the Operation of the Provisions

- Objective 3: Recommended Changes to Reduce or Eliminate Sex-Based Inequities

- Impacts of Implementation of the Provisions to Date

- Communications and Engagement

- Processing and Policy Changes

- Next Steps

- ANNEXES

- Annex A – Review of Section 6 (first phase - 2017)

- Annex B - The removal of the "1951 Cut-off"

- Annex C – Overview of Current Sections 6(1) and 6(2) of the Indian Act

- Annex D—First Nations Bands Represented at Broader Reform Events

- Annex E—Bilateral First Nations Participants

- Annex F—First Nations Participants at Departmental Training

Message from the Minister

It is my pleasure to present the 2020 report on the review of the implementation of S-3, the last of 3 reports mandated in S-3: An Act to amend the Indian Act, in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

S-3 received Royal Assent on December 12, 2017 with many provisions put in force on December 22, 2017. On August 15, 2019 the last remaining provision was brought into force by order of the Governor in Council, advancing our work on gender equality and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. These last changes removed the "1951 cut-off" from the Indian Act. The removal of the cut-off aligns patrilineal and matrilineal lines and ensures that descendants born prior to April 17, 1985 (or of a marriage before that date) of women who lost status or were removed from band lists because of their marriage to non-status men going back to 1869 are entitled to registration under the Indian Act.

S-3 corrects historical wrongdoings in the registration provisions of the Indian Act that have affected women and their descendants for generations and is a testament to the perseverance and advocacy of Indigenous women, leaders and allies over decades. The removal of the "1951 cut-off" responds to longstanding concerns raised by First Nations People, the United Nations Humans Rights Committee, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and other key stakeholders.

It is estimated that the full implementation of S-3 could result in 270,000 to 450,000 newly registered individuals in total. To date, more than 10,000 individuals have been newly registered. In addition, 57,000 individuals who were already registered and were unable to pass on their entitlement to their descendants are now able to do so due to category amendments made between 2019 and 2020.

While sex-based inequities in the registration provisions have been eliminated, residual impacts from years of sex-based inequities continue to be felt in the registration context today. Additionally, other non sex-based inequities still remain in the Indian Act and the department continues to work with First Nations and Indigenous partners on how best to address these concerns.

The implementation of S-3 is an important shift towards confronting Canada's history and redressing the historical wrongs. It is a shift that ensures that Canada continues to renew and rebuild its relationship with Indigenous Peoples based upon the affirmation of rights, respect, cooperation and partnership.

Executive Summary

- In 2016, Bill S-3 An Act to amend the Indian Act in Response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux was introduced in Parliament in direct response to a court decision which found that some registration provisions of the Indian Act violated equality rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

- S-3 partially came into force in 2017 to address the sex-based inequities identified by the court, as well as additional sex-based inequities raised by Indigenous women, leaders and allies.

- Following consultation with First Nations, further amendments removing what is referred to as the "1951 cut-off" came into force in August 2019 and eliminated all sex-based inequities in registration.

- While sex-based inequities in registration have been eliminated, the department recognizes that there are residual impacts of these historical sex-based laws and their effects that continue to affect registration.

- Registration provisions for patrilineal and matrilineal lines going back to 1869 are now aligned. Those newly eligible include grandchildren born prior to September 4, 1951 of women who were removed from their First Nation's band list or lost status because of their marriage to a non-Indian man. Now, descendants born prior to April 17, 1985 (or of a marriage before that date) of women who lost status or were removed from band lists because of their marriage to non-status men going back to 1869 are entitled to registration under the Indian Act.

- Pursuant to S-3, the Minister is responsible for tabling three reports to Parliament. The first report, tabled on May 12, 2018 reported on the design of a Collaborative Process on Indian Registration, Band Membership and First Nation Citizenship. The second report, tabled on June 12, 2019 reported on the findings of that Collaborative Process.

- S-3 outlines the objectives on which the third and final report must focus:

- A determination as to whether any sex-based inequities remain in section 6, the registration provisions, of the Indian Act;

- A review of the operation of the provisions of the Indian Act that are enacted by S-3; and

- If the Minister determines that any sex-based inequities still exist with respect to the provisions of section 6 of the Indian Act enacted by S-3, a statement of any recommended changes to the Indian Act must be provided in order to reduce or eliminate those sex-based inequities.

- The report presents the following findings:

- It has been determined that sex-based inequities in the registration provisions of the Indian Act have been eliminated.

- At the 3-year mark, the department has seen one third of the S-3 applications it had initially anticipated and the number of newly registered individuals is also lower than expected. As a result, the impacts to date to programs and services associated with registration under the act are minimalFootnote 1.

- While sex-based inequities have been eliminated from registration, the department recognizes that residual effects of these previous sex-based inequities and non sex-based inequities in the registration provisions persist, including: the "second-generation cut-off," scrip, and enfranchisement. Registration and its link to band membership is also a concern for many individuals and First Nations. Engagement with First Nations and stakeholders is ongoing to determine how best to address these concerns.

- To date, more than 10,000 individuals have been successfully registered as a direct result of the changes to the registration provisions. The department has an inventory of 12,000 applications still requiring review. Although productivity early in the COVID-19 pandemic was reduced, processing has now returned to pre-COVID levels.

- The department is working to improve the client experience, address delays in registration decisions and raise awareness among those who are newly entitled.

- Specifically, the department is:

- making a number of processing and policy changes to enhance and modernize operations such as a digital tool to move away from paper-based applications;

- investing $15.4 million to scale up processing;

- investing an additional $5.8 million on engagement, outreach and monitoring of impacts.

- It is important for Canada to continue to cultivate its commitment to a renewed relationship with Indigenous Peoples based upon the affirmation of rights, respect, cooperation and partnership. Going forward, the department must continue to address these outstanding concerns to ensure that the department is on the path to "getting out of the business of Indian registrationFootnote 2."

Introduction

This report fulfills the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada's obligation under S-3 to report after 3 years on the review of S-3: An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

As required by S-3, this report reviews whether any sex-based inequities remain in the registration provisions, reviews the operation of the provisions enacted by S-3 and the aligning of matrilineal and patrilineal lines going back to 1869. The report also determines that, while no sex-based inequities remain, ongoing and residual effects of the previous sex-based legislation and policy and non-sex-based inequities persist.

The department recognizes that it faces many challenges in redressing historical wrongs in the Indian Act. Further, it recognizes that the disconnection resulting from these wrongs and their residual effects have disproportionality impacted the descendants of Indigenous women, many who may not know that they're now entitled to registration. The department is committed to ongoing outreach and timely access to programs and services for those newly entitled.

COVID-19

In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic. Following instructions from public health agencies, the federal government issued work-from-home orders.

As a result, the COVID-19 pandemic has created operational challenges for the department in the implementation of S-3, including its commitment to continue discussions on the remaining inequities of the Indian Act and its obligation to process applications for registration. Because of the paper-based, mail-in nature of applications for registration, productivity early in the pandemic was reduced. Processing has now returned to pre-COVID levels. Alternative virtual environments are being established to deliver on commitments relating to engagement, outreach and the monitoring of impacts.

Background on Sex-Based Inequities in the Indian Act

Since the 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act and with the implementation of the first Indian Act in 1876, the federal government has exercised exclusive statutory authority in determining the definition of IndianFootnote 3 and therefore eligibility to Indian registration (Indian status) under the Indian ActFootnote 4. This authority is exercised through the Office of the Indian Registrar. Under the Indian Act, status Indians, also known as registered Indians, may be eligible for a range of benefits, rights, programs and services offered by the federal and provincial or territorial governments.

Section 6 of the Indian Act sets out requirements for entitlement to registration as an Indian. Eligibility to Indian status is determined on the basis of an individual's descent from a person registered or eligible to be registered as an Indian. Applicants must establish a link to Canadian Indian ancestry based upon documentary evidence such as a birth certificate.

Since the 19th century, women and their descendants have been discriminated against due to sex-based inequities in legislation related to registration and band membership under the Indian Act. Beginning in 1869 with the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, the definition of Indian was no longer based on First Nations kinship and community ties. Instead, it built on the predominance of men over women and children and aimed to remove families headed by a non-Indian man from First Nations communitiesFootnote 5. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act also introduced the "marrying out rule" that was maintained in the 1876 Indian Act. This rule removed entitlement to registration from Indian women who married non-Indian men, while granting entitlement to non-Indian women who married Indian men. In addition, children of entitled men who married non-Indian women became entitled under the Indian Act, while children of women who "married out" were no longer entitledFootnote 6.

In 1951, substantial changes with respect to registration were made including the creation of a centralized Indian Register. Further amendments reinforcing discrimination against women and their descendants were made, including the "double mother" ruleFootnote 7.

Sex-based discrimination in the act has been challenged in light of national and international human rights legislation, including the removal of women from First Nations communities and their inability to retain their Indigenous identity in the eyes of Canadian law. For decades, Indigenous women have fought for equal rights under the law and challenged the patriarchal provisions of the Indian Act. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Jeanette Lavell of Wikwemkoong, Yvonne Bédard of Six Nations of the Grand RiverFootnote 8, elder-activist Mary Two Axe Earley of Kanien'kehá:kaFootnote 9, and Senator Sandra Lovelace Nicholas of Maliseet NationFootnote 10 brought various challenges against the act for its discrimination against women and their descendants.

In 1985, with the 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms coming into force and increased international pressure, C-31 An Act to Amend the Indian Act was enacted.

C-31 introduced changes to the Indian Act that:

- would address sex-based inequities and remove:

- the "marrying out" rule

- the "double mother" rule

- "voluntary" or involuntary enfranchisement and

- the ability to be removed via protest due to non-Indian paternityFootnote 11.

- reinstated entitlement to registration to:

- individuals affected by the "double mother" rule

- women who had lost status or who were no longer recognized under the Indian Act when they married a non-Indian man.

- maintained the status of all individuals who were entitled immediately prior to the passage of the act by virtue of section 6(1)(a) including women who had gained status due to their marriage to an entitled man.

- created five entitlement categories under section 6(1) and introduced the "second generation cut-off" under section 6(2)Footnote 12.

Although this was an important step toward the elimination of sex-based inequities in the Indian Act, C 31 did not address all sex-based inequities. In 2007, lawyer and activist Dr. Sharon McIvor of Nle?kepmxc Nation and her son Jacob Grismer challenged the act by revealing that sex-based inequities remained. Women who had lost their status as a result of marrying a non-Indian man and who were reinstated under section 6(1)(c) were unable to pass on entitlement to their grandchildren while Indian men who married non-Indian women were still able to pass on entitlement to their grandchildren. In 2009, the British Columbia Court of Appeal agreed with Dr. McIvor and found that these aspects of the act were contrary to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and were discriminatory based on sexFootnote 13.

In response to this court decision, C-3 the Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act was adopted in 2011 and created the provision 6(1)(c.1). This new provision established the entitlement of the grandchildren of women who married non-Indian men. C-3 also introduced the "1951 cut-off" to fix the "double mother" rule created in 1951. The "1951 cut-off" required that an individual must have had a child or adopted a child on or after September 4, 1951 and have a mother who lost entitlement due to a marriage to a non-Indian man, to be registered under 6(1)(c.1)Footnote 14. However, C-3 did not resolve the inequities in entitlement for further descendants of women compared to descendants of men in similar circumstances. This resulted in further litigation against CanadaFootnote 15.

In the 2015 Descheneaux decisionFootnote 16, the Superior Court of Quebec ruled that the act violated equality rights under the Charter by continuing sex-based differences in registration. In the 2017 Gehl decisionFootnote 17, the Ontario Court of Appeal supported Dr. Lynn Gehl, an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe and determined that women were unfairly disadvantaged by the Indian Registrar's policy with respect to unstated or unknown parentage. In 2017, to address these persisting sex-based inequities, Parliament with the support of important work by Indigenous organizations and leaders, such as former Senator Lillian Dyck, brought into force S-3 An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

These legislative changes were implemented in 2 phases.

Phase 1:

The first phase (Annex A) of the implementation included immediate amendments to the Indian Act to address the following sex-based issues:

- The "cousins" issue: differential treatment of first cousins whose grandmother lost status due to marriage to a non-Indian man before April 17, 1985.

- The "siblings" issue: differential treatment of women who were born outside of marriage to entitled fathers between September 4, 1951 and April 17, 1985.

- The issue of omitted minor children: differential treatment of minor children who were born of an entitled mother and an entitled father between September 4, 1951 and April 17, 1985, but could lose entitlement to status if they were still minors at the time of their mother's subsequent marriage to a non-Indian man.

- The unstated or unknown parent issue: in response to the Ontario Court of Appeal's Gehl decision, S-3 provides flexibility for the Indian Registrar to consider various forms of evidence in determining eligibility for registration in situations of an unstated or unknown parent, grandparent or other ancestor.

On December 22, 2017, the first phase of S-3 came into force and introduced the new sections of 6(1)(c) entitlement categories for newly eligible individuals (hereafter referred to as 6(1)(c) provisions).

The first phase of the bill left in place the "1951 cut-off" until consultation with First Nations and stakeholders and impacted individuals occurred.

Phase 2:

The second phase of the implementation of the S-3 provisions addressed the "1951 cut-off" by removing it, ensuring the entitlement of all descendants of women who lost status or were removed from band lists for marrying a non-Indian man going back to 1869, when the Gradual Enfranchisement Act was introduced. Due to the projected impacts on First Nations, there was a delay in removing the "1951 cut-off" to allow for consultations. Between 2018 and 2019, during the Collaborative Process on Indian Registration, Band Membership and First Nation Citizenship, First Nations were consulted on the removal of the cut-off as well as broader issues relating to the Indian Act. The 2019 Report to Parliament on Indian Registration, Band Membership and First Nation Citizenship indicated general agreement for the removal of the "1951 cut-offFootnote 18."

On August 15, 2019, S-3 was brought fully into force to remove the "1951 cut-off" (see Annex B for how these amendments broadened eligibility). All 6(1)(c) provisions of the Indian Act were repealed or replaced with new 6(1)(a) provisions. These amended provisions now recognize descendants of women who married non-Indian men the same as descendants of men who married non-Indian women.

Objective 1: Reviewing the Elimination of Sex-Based Inequities

Section 12(1)(a)(i) of S-3 mandates a determination as to whether any sex-based inequities remain in the registration provisions of the Indian Act.

It has been determined that S-3 amendments address the inequities as outlined by the Descheneaux decision as well as the sex-based inequities with respect to unstated and unknown parentage. The provisions in section 6 of the Indian Act no longer privilege one sex or gender over another. The amendments go beyond addressing the "double mother" rule and work to align the entitlement of descendants of men and women going back to the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, specifically addressing cases where women were removed from First Nations and band lists for their marriage to a non-Indian man. As a result, all sex-based inequities previously in section 6 of the Indian Act have been eliminated (See Annex C); however, the department recognizes that there are residual impacts of these historical sex-based laws and their effects that continue to affect registration (See Objective 3).

Additionally, clause 9 of S-3 provides that the amended provisions of the Indian Act are to be liberally construed and interpreted so as to remedy any disadvantage to a woman, or her descendants, born before April 17, 1985 with respect to registration under the Indian Act as it read on April 17, 1985Footnote 19. As such, clause 9 works to enhance the equal treatment of women and men and their descendants under the Indian Act.

Objective 2: Review of the Operation of the Provisions

Section 12(1)(a)(ii) of S-3 mandates a review of the operation of the provisions of the Indian Act that are enacted by S-3.

As a result of S-3 coming into full force on August 15, 2019, section 6 of the Indian Act has been renumbered and some paragraphs have been repealed. The following charts outline the current legislative language of relevant provisions of the Indian Act and provide a description of the standardized interpretation and application.

Section 5: Legislative Language and Interpretation

| Legislative Language | Interpretation |

|---|---|

Subsection 5(6) Unknown or unstated parentage |

|

Subsection 5(7) |

|

Section 6: Legislative Language and Interpretation

| Legislative Language | Interpretation |

|---|---|

Paragraph 6(1)(a) (a) that person was registered or entitled to be registered immediately before April 17, 1985; |

|

Paragraph 6(1) (a.1) the name of that person was omitted or deleted from the Indian Register or from a band list before September 4, 1951, under subparagraph 12(1)(a)(iv), paragraph 12(1)(b) or subsection 12(2) or under subparagraph 12(1)(a)(iii) pursuant to an order made under subsection 109(2), as each provision read immediately before April 17, 1985, or under any former provision of this act relating to the same subject matter as any of those provisions; |

|

Paragraph 6(1)(a.2) |

|

Paragraph 6(1)(a.3) |

|

Paragraph 6(1)(f) |

|

Subsection 6(2) |

|

Subsection 6(2.1) |

|

Subsection 6(3) |

|

Section 11: Legislative Language and Interpretation

| Legislative Language | Interpretation |

|---|---|

Membership rules for Departmental Band List (a) the name of that person was entered in the band list for that band, or that person was entitled to have it entered in the band list for that band, immediately prior to April 17, 1985; (b) that person is entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(b) as a member of that band; (c) that person is entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(a.1) and ceased to be a member of that band by reason of the circumstances set out in that paragraph; or (d) that person was born on or after April 17, 1985 and is entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(f) and both parents of that person are entitled to have their names entered in the band list or if no longer living, were at the time of death entitled to have their names entered in the band list. |

|

Subsection 11(3) (3) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(d) and subsection (2), (a) a person whose name was omitted or deleted from the Indian Register or a band list in the circumstances set out in paragraph 6(1)(a.1), (d) or (e) and who was no longer living on the first day on which the person would otherwise be entitled to have the person's name entered in the band list of the band of which the person ceased to be a member is deemed to be entitled to have the person's name so entered; (a.1) a person who would have been entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(a.2) or (a.3), had they been living on the day on which that paragraph came into force and who would otherwise have been entitled, on that day, to have their name entered in a band list, is deemed to be entitled to have their name so entered; and (b) a person described in paragraph (2)(b) shall be deemed to be entitled to have the person's name entered in the band list in which the parent referred to in that paragraph is or was or is deemed by this section to be entitled to have the parent's name entered. |

|

Subsection 11(3.1) (3.1) A person is entitled to have their name entered in a band list that is maintained in the department for a band if (a) they are entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(a.2) and their father is entitled to have his name entered in the band list or, if their father is no longer living, was so entitled at the time of death; or (b) they are entitled to be registered under paragraph 6(1)(a.3) and one of their parents, grandparents or other ancestors (i) ceased to be entitled to be a member of that band by reason of the circumstances set out in paragraph 6(1)(a.1), or (ii) was not entitled to be a member of that band immediately before April 17, 1985. (c) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (d) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (e) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (f) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (g) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (h) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] (i) [Repealed, 2017, c. 25, s. 3.1] |

|

Section 64: Legislative Language and Interpretation

| Legislative Language | Interpretation |

|---|---|

Subsections 64.1(1) and (2) Expenditure of capital moneys with consent 64.1(1) A person who has received an amount that exceeds $1,000 under paragraph 15(1)(a), as it read immediately before April 17, 1985 or under any former provision of this act relating to the same subject matter as that paragraph, by reason of ceasing to be a member of a band in the circumstances set out in paragraph 6(1)(a.1), (d) or (e) is not entitled to receive an amount under paragraph 64(1)(a) until such time as the aggregate of all amounts that the person would, but for this subsection, have received under paragraph 64(1)(a) is equal to the amount by which the amount that the person received under paragraph 15(1)(a), as it read immediately before April 17, 1985 or under any former provision of this act relating to the same subject matter as that paragraph, exceeds $1,000, together with any interest. Expenditure of capital moneys in accordance with by-laws (2) If the council of a band makes a by-law under paragraph 81(1)(p.4) bringing this subsection into effect, a person who has received an amount that exceeds $1,000 under paragraph 15(1)(a), as it read immediately before April 17, 1985 or under any former provision of this act relating to the same subject matter as that paragraph, by reason of ceasing to be a member of the band in the circumstances set out in paragraph 6(1)(a.1), (d) or (e) is not entitled to receive any benefit afforded to members of the band as individuals as a result of the expenditure of Indian moneys under paragraphs 64(1)(b) to (k), subsection 66(1) or subsection 69(1) until the amount by which the amount so received exceeds $1,000, together with any interest, has been repaid to the band. |

Paragraph 64.1(1) relates to individuals who received per capita distribution or bulk treaty payments upon certain enfranchisement under former Indian Acts (prior to C-31 coming into effect in 1985). If those individuals, who've been reinstated under paragraphs 6(1)(a.1), (d) or (e) received amounts exceeding $1000, they would only be entitled to capital moneys paid from the surrender of land if it exceeds the total they received upon enfranchisement plus interest. Paragraph 64(1)(2) relates to individuals who received per capita distribution or bulk treaty payments upon certain enfranchisement under former Indian Acts (prior to C-31 coming into effect in 1985). If those individuals, who've been reinstated under paragraphs 6(1)(a.1), (d) or (e) received amounts exceeding $1000, they would only be entitled to an individual benefit of capital moneys in accordance with band by-laws enacted under the various sections if it exceeds the total they received upon enfranchisement plus interest. |

Objective 3: Recommended Changes to Reduce or Eliminate Sex-Based Inequities

Section 12(1)(b) of S-3 indicates that if the Minister determines that any sex-based inequities still exist with respect to the provisions of section 6 of the Indian Act enacted by S-3, a statement of any recommended changes to the Indian Act must be provided in order to reduce or eliminate those sex-based inequities.

As it has been determined that sex-based inequities in the registration provisions of the act have been eliminated, there are no recommended changes with respect to sex-based inequities in the provisions of section 6 of the Indian Act enacted by S-3.

However, while sex-based inequities have been eliminated from the registration provisions, the department recognizes that 150 years of discriminatory laws and policies and the resulting sex-based inequities created residual effects that continue to be felt in the registration context today. Ongoing concerns regarding timely access to rights, services, and benefits; as well as retroactive treaty benefits, reparations, and issues of band membership; and the ways that other provisions of the Indian Act intersected with these historic laws and policies have been raised by Indigenous women and leaders.

Moreover, there are non sex-based inequities that continue to persist in registration provisions of the Indian Act including enfranchisement, scrip, and "second generation cut-off." There are also First Nation membership and citizenship concerns. These will require legislative changes and the department continues to engage with First Nations and Indigenous partners on how best to address these issues.

The department is taking steps to address inequities in registration. Most recently, the Hele decisionFootnote 20 found that the Indian Registrar did not have the authority to enfranchise an unmarried Indian woman by application between 1951 and 1985. In response, the department addressed those directly involved in the litigation or similar litigations. Steps are currently being taken to review the additional impacts of the decision and identify other women and their descendants who may be affected in order to address the situation. This includes reviewing women registered or entitled to be registered under 6(1)(d) in the Indian Act, and their descendants.

Work continues on both the residual impacts of sex-based discrimination and the non sex-based inequities in registration.

Impacts of Implementation of the Provisions to Date

Projected Demographic Information

Under the first phase of S-3, it was estimated that the department would see 43,000 applications resulting in up to 35,000 new registrations over 5 years.

Under the second phase (the removal of the "1951 cut-off"), it was estimated the department would see between 330,000 and 553,000 applications resulting in approximately 270,000 to 450,000 new registrations over 10 years.

It's expected that it will take longer for people impacted by the removal of the "1951 cut-off" to apply given that in many of those affected by the "cut-off" experience disconnection from resources, programs, services, reserve land and ethno-cultural integration. These disconnections are residual impacts of the historical sex-based inequities. People now eligible for registration may not know that they're entitled because they're unaware of their First Nations ancestry. Even when ancestry is known, it's often difficult for applicants to access genealogical documentation.

Impacts to Date

Applications and Registrations

It was anticipated that within the first 3 years of implementation, the department would receive approximately 78,500 applications. Between December 2017 and November 2020, the department received approximately 28,000 applications identified as S-3Footnote 21. Of the 28,000 applications submitted, approximately 48% have been fully processed, resulting in 10,800 registrations. Approximately 9% of the remaining applications have been partially processedFootnote 22, and 43% or approximately 12,000 are currently in the inventory awaiting reviewFootnote 23.

The department acknowledges the impacts of the delays in registration and is taking steps to modernize the process to make it more efficient and client-centered. The department continues to monitor application and registration numbers.

Band Membership

The department recognizes the varying perspectives raised by First Nations on the ways S-3 could impact band membership. Considering that First Nations band membership provides access to band programs and services, rights such as voting rights and the ability to live on-reserve, the estimated increase of newly registered population as a result of S-3 will have an impact on band membership for First Nations whose band lists are maintained by the departmentFootnote 24. However, given the low number of newly registered individuals to date, no considerable impacts have been identified in communities.

While section 10 of the Indian Act allows bands to develop their own band membership rules and assume control of their membership lists, S-3 could impact intentions of this provision given current requirements, which include notice and consent of a majorityFootnote 25 of eligible electors and the protection of acquired rights. These requirements compel First Nation bands to engage all eligible electors in an equal manner before adopting their own membership rules, including those newly entitled under S-3 who are likely to live off-reserve and may have little community connection.

The department continues to monitor and engage First Nations on the impacts of S-3 on band membership and citizenship.

On- and Off-Reserve Mobility

The department has been monitoring First Nations band population numbers and growth since the implementation of S-3. Based on lessons learned from past amendments to registration provisions, S‑3 is anticipated to have negligible impacts overall to both on- and off-reserve mobility trends. At this time, there have been no significant changes to First Nations band population numbers or on-reserve mobility trends.

Automated Amendments

In 2019, the department automated category amendments for already registered individuals to align with the new registration provisions. As a result, 124,000 individuals have had their registration category amended in the Indian Register. Of these amendments, 57,000 individuals who were previously registered under 6(2) were subsequently amended to registration under 6(1) as a result of S-3. These individuals are now able to transmit status to their descendants where they were ineligible before due to the "second-generation cut-off" provision. At least one subsequent generation from these individuals is now eligible for registration under the Indian ActFootnote 26.

Impacts on Departmental Programs and Services that are accessible by those newly entitled

The first 3 years of the implementation of S-3 have not yielded funding pressures on programs linked to Indian statusFootnote 27. However, the department is monitoring registration rates in order to ensure resources be made available should it be determined that S-3 has resulted in additional pressures to programs.

Communications and Engagement

Communications

With the coming into force of S-3 in December 2017, a communications plan for the Collaborative Process on Indian Registration, Band Membership and First Nation Citizenship with First Nations and Indigenous organizations was developed and implemented in 2018 and 2019. As outlined in the 2019 report to Parliament, the Collaborative Process outreach was extensive and included information sessions, regional events, community events, expert panels, funding for organizational participation and an online survey specifically targeted to urban populationsFootnote 28.

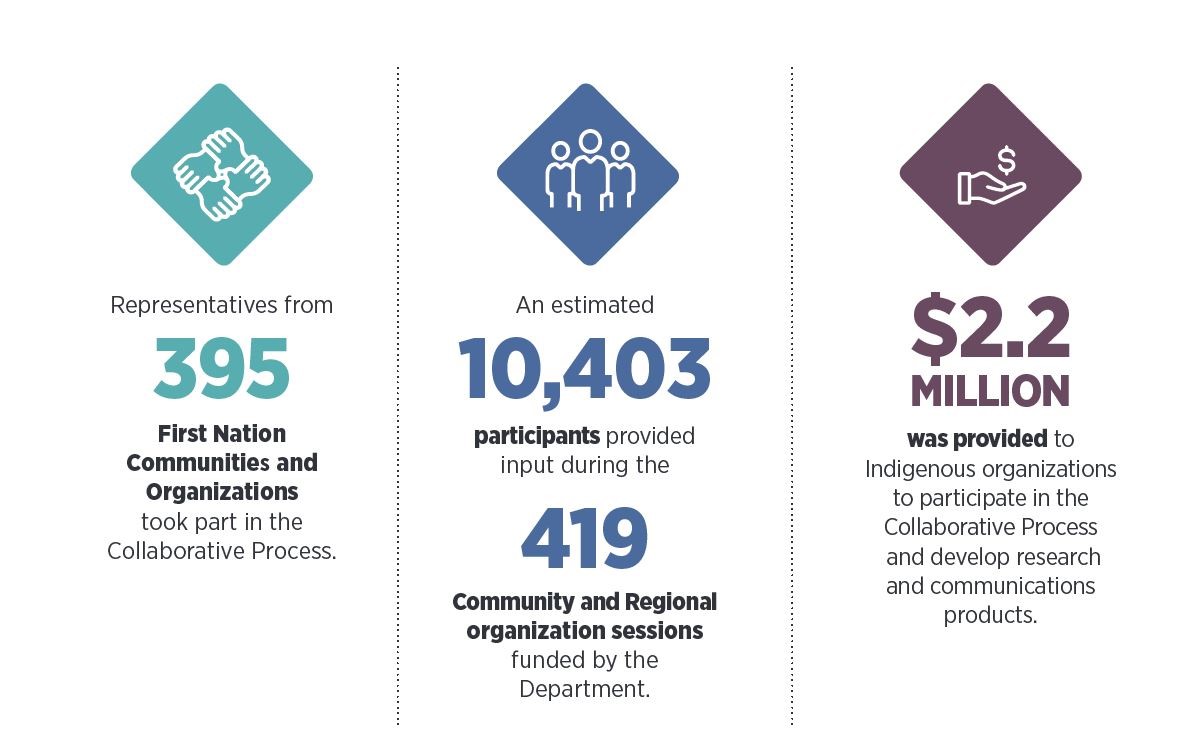

Long description for figure 1: Communication and Engagement Infographic

This infographic highlights that representatives from 395 First Nation communities and organizations took part in the Collaborative Process, an estimated 10,403 participants provided input during the 419 community and regional organization sessions funded by the department and $2.2 million was provided to Indigenous organizations to participate in the Collaborative Process and develop research and communications products.

Information and training sessions were organized, phone inquiries were fielded and additional funding was provided to Indigenous organizations for outreach, research and communications materials (see engagement section below).

Updates were provided through social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, web pages and 3 ministerial announcements. Local and national media, including APTN, Nation Talk, CBC, The National Post, Le Devoir, The Globe and Mail and Maclean's reported on S-3 developments.

Engagement

Throughout the engagement process, remaining inequities in the registration provisions of the Indian Act were raised including issues of the "second-generation cut-off", scrip and enfranchisement. The department continues to work in partnership with First Nations to address these remaining concerns and to ensure the department remains on the path to "getting out of the business of Indian registration."

After the completion of the Collaborative Process in April 2019, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada engaged with First Nations communities and organizations during a series of information and discussion sessions entitled "Broader Reform Events" in early 2020. These events provided updates on the full implementation of S-3, discussed the input collected during the Collaborative Process and highlighted general information on what Canada would be undertaking as next steps in relation to the inequities in registration and First Nation citizenship. Invitations to attend the Broader Reform Events were sent to 744 First Nations bands and other First Nations stakeholders. Of the 19 sessions that were held over 200 First Nations bands were represented (Annex D)Footnote 29.

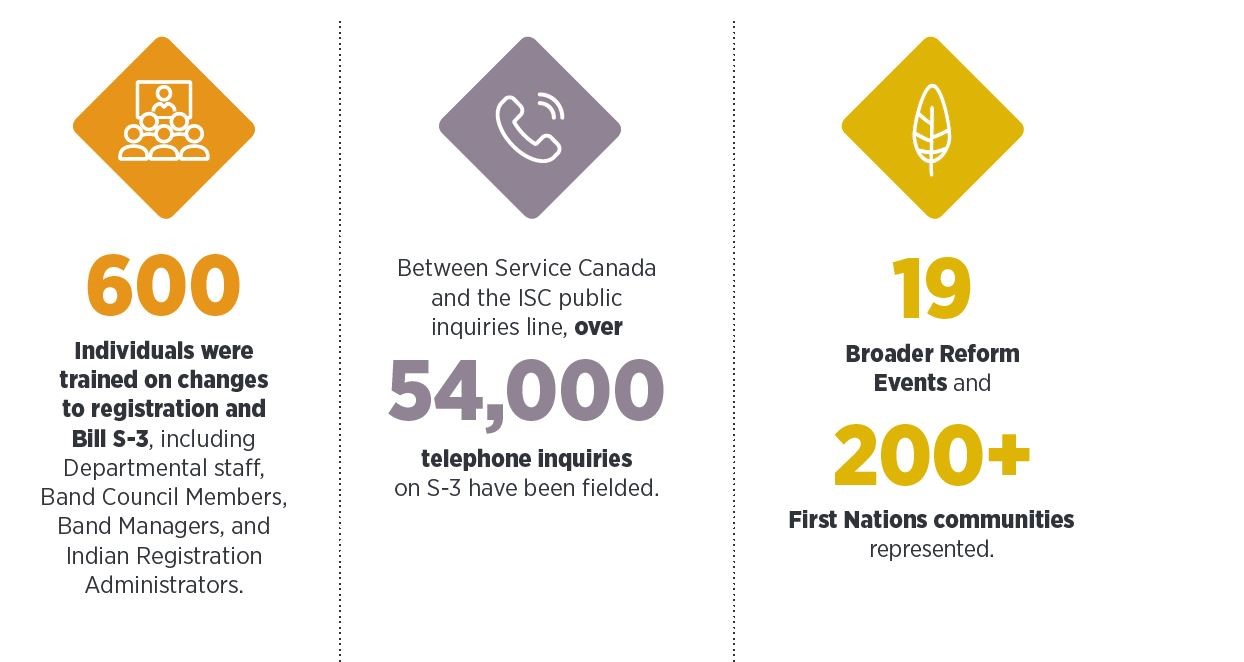

Long description for figure 2: Communication and Engagement Infographic

This infographic highlights that 600 individuals were trained on changes to registration and Bill S-3, including departmental staff, band council members, band managers and Indian Registration Administrators. Between Service Canada and the Indigenous Services Canada public inquiries line, over 54,000 telephone inquiries on S-3 have been fielded. 19 Broader Reform Events took place and more than 200 First Nations communities represented.

Further engagement occurred throughout 2020 on topics including impacts to communities, newly entitled individuals and registration category amendments. Due to the ongoing pandemic, in-person meetings were not possible. Between August and November 2020, Indigenous Services Canada held meetings with over 100 First Nations via teleconference or videoconference through bilateral engagements and additional training sessions (Annexes E and F). Indigenous Services Canada has begun and continues to work with provinces and territories to better understand any S-3 impacts to the provision of programs and services to registered individuals and communities. Engagement on these and other inequities will be ongoing throughout the 2020-2021 fiscal year and beyond, including a public facing communications and outreach plan.

The department continues to seek partnerships with Indigenous organizations including the Assembly of First Nations and Native Women's Association of Canada to engage as broadly as possible on outstanding inequities in registration. This important work will be used to develop solutions to bring forward to First Nations and other stakeholders.

Processing and Policy Changes

To deliver on S-3 commitments, including the timely processing of applications for those newly entitled, the department continues to take steps to improve upon its internal and client-facing processes.

Since 2017, the department has committed over $40 million towards S-3. This includes making a number of processing and policy changes to enhance and modernize operations; over $30 million in scaling up processing capacity; and over $10 million on engagement, outreach and monitoring of impacts. All of these investments aim to improve the client experience and ensure applicants receive timely access to programs and services.

To date, the department has put in place or is in the process of putting in place the following:

- enhanced processing capacity to support an increase in applications. In addition to ramping up processing capacity in the Winnipeg Processing Unit, a secondary Quebec City Processing Unit is being established to enhance overall capacity to render entitlement decisions and further support the processing of applications for French speaking clients.

- integrated registration and collection of individuals' ancestral information to the great-grandparent level. Doing so improves the department's ability to research and determine entitlement and ensures clarity in ancestry and facilitates faster file processing for subsequent generations. Integration of the applications means that there is no duplication in the registration process and ensures ease of access to the Secure Certificate of Indian Status which facilitates access to benefits and services specific to the applicant's status.

- advanced digital tool to modernize the department's application process for both registration and SCIS. This tool provides an essential shift away from paper-based applications to a more modern and streamlined digital in-person application form.

- reduced the number of applicants needing to reapply by holding applications for those eligible under the removal of the "1951 cut-off" instead of denying them in the first phase of S-3. In doing so, applicants maintained their place in the processing queue.

- proactively amended category codes to reflect the new legislation, for example 6(1)(c) to 6(1)(a.1). Since 2017, the automated amendments resulting from S-3 have been completed in the Indian Registration System, benefiting approximately 124,000 individualsFootnote 30.

- simplified the application process and processing requirements including a less prescriptive and more flexible approach to documentation and evidence to support application on the balance of probabilities. All forms of acceptable evidence can be submitted to demonstrate entitlement to status and increased subjectivity during the review process allows for flexibility in assessment of documentation. The department continues to work towards making the application process more client-centered.

- introduced new guidance and tools for departmental staff to address complex cases such as unstated and unknown parentage cases and to provide guidance to decision makers on how to render decisions based on the balance of probabilitiesFootnote 31. Mandatory training from the Department of Justice was completed by departmental staff reinforcing the balance of probabilities approach in decision making.

- updated guidance and training for departmental staff across the regions, resulting in more consistency in training and improved understanding of the applicability of the amendments.

- priority processing of persons over 75 years of age with applications in the queue to ensure that the elders who may have the lived experience of discrimination caused by sex-based inequities in the provisions of the act have their applications processed efficiently.

- digitized records in order to access an applicant's information and family genealogy faster. The department has a large digital collection of historical records that will yield improved service to applicants born pre-1951 and their descendants.

- implemented non-binary gender identifiers on both registration and Secure Certificate of Indian Status applications and soon on the physical card of the Secure Certificate of Indian Status itself.

- leveraged existing agreements with provincial Vital Statistics Agencies to reduce the burden on applicants who need to acquire information about their birth, their families and their ancestry. This is an ongoing effort and one that the department will continue to raise with provinces and territories as we collectively monitor the impact of S-3.

- developed partnerships with First Nations organizations, Canada Post Corporation and Correctional Services Canada to reduce redundancies in application requirements and facilitate efficient client-centered services.

Long description for figure 3: Processes and Policy Changes Infographic

This infographic highlights the process and policy changes discussed in the report. Changes have generated 124,000 automated category amendments, reduced the number of applicants needing to apply, integrated registration and Secure Certificate of Indian Status applications, developed new unstated and unknown parentage policy and started priority processing of persons over 75 years of age with applications in the queue. ISC has invested $40 million for resources, monitoring and engagement, created the Quebec City Processing Unit, updated and created new training materials for officers, advanced digital tool to modernize the application process and digitized records. Further, Indigenous Services Canada has leveraged agreements with Vital Statistics Agencies, implemented non-binary gender identifiers on applications, developed partnerships with First Nations Organizations, Canada Post Corporation and Corrections Services of Canada and produced flexible documentation requirements.

Next Steps

Although S-3 has resulted in the removal of known sex-based discrimination in the registration provisions, there is more to be done to address concerns and redress the effects of historic policy and law. Next steps include:

Continued work with partners and advocates on outreach and communications

Feedback makes it clear that S-3 and its provisions are not well understood. The department will continue its communications efforts and outreach plan addressing S-3 and how the new legislation may impact individuals who are registered or could be entitled to registration under the Indian Act. Continued engagement with First Nations is necessary to understand and monitor the impacts of S‑3 over time. The department will continue its outreach to urban communities and Indigenous organizations to ensure that those who may not yet know that they're newly entitled to registration are aware of the legislative changes and are provided the opportunity and support to apply.

Address the unnecessary delays in registration

The department recognizes that unnecessary delays in registration exist and impact equitable access to benefits and services especially for those who are newly entitled under S-3. There will be an improvement in processing capacity resulting from the establishment of the Quebec City Processing Unit and ramping up capacity in the existing Winnipeg Processing Unit. The department will continue to advance efficiencies to improve client experience and reduce wait times for rendering decisions on entitlement, while implementing a national workload strategy to ensure consistent client-centered service standards regardless of point of application across the country. The department will continue to monitor impacts, engage First Nations and report back on any funding related pressures.

Address the remaining inequities in registration

Moving forward, the department continues to take steps to address the remaining inequities in registration under the Indian Act. Using the research and information from First Nations partners and stakeholders, the department will continue to collaborate on solutions and any necessary amendments to the registration provisions of the Indian Act to ensure that the department remains on the path to "getting out of the business of Indian registration."

ANNEXES

Annex A – Review of Section 6 (first phase - 2017)

As a result of the Government of Canada's Response to the Descheneaux Decision and the phase 1 amendments that came into force in December 2017, the S-3 amendments aligned matrilineal lines with patrilineal lines as it related to:

- the "Cousins Issue"

- the "Siblings Issue"

- the "Omitted Minors Issue"

- the issue of children born outside of legal marriage to an Indian mother and non-Indian father

- the issue of Great-Grandchildren affected by the "Double-Mother Rule"

- the issue of Great-Grandchildren Born Pre-1985 of a Parent Affected by the "Siblings Issue"

- the issue of Great-Grandchildren, Born Pre-1985, Whose Indian Great-Grandmother Parented Out of Wedlock with a Non-Indian

- 6(1)(c) has been amended to 6(1)(a.1)

- 6(1)(c.3) has been amended to 6(1)(a.2) and

- all other 6(1)(c) paragraphs have been amended to 6(1)(a.3)

- some descendants of parents married prior to 1985 will now be entitled under 6(1)(a.3).

Annex B - The removal of the "1951 Cut-off"

The removal of the "1951 cut-off" has resulted in changes to entitlement. Various amendments in the Indian Act corrected sex-based inequities that stemmed from the previous law that caused women to lose their status or be removed from First Nations band lists because of they married non-Indian men.

In the first implementation phase of S-3 (2017), only the grandchildren born on or after September 4, 1951 of women who were removed from their First Nation's band list or lost status because of they married a non-Indian man became entitled under a 6(1) category allowing entitlement to flow to their direct descendants.

Grandchildren born before September 4, 1951 of women who were removed from their First Nation's band list or who lost status because they married a non-Indian man were reinstated in the second implementation phase (2019) after consultations with First Nations and other stakeholders.

It's important to note that the S-3 amendments did not remedy the "second-generation cut-off." This is a non sex-based inequity. Conversations with First Nations and Indigenous partners on how best to address this issue are ongoing.

Annex C – Overview of Current Sections 6(1) and 6(2) of the Indian Act

| 6(1)(a) | Entitlement of person who was registered or entitled to be registered on or before April 17, 1985. |

| 6(1)(a.1) | Reinstatement of individuals whose names were omitted or deleted from the Indian Register or a band list prior to September 4,1951, because of:

the person was removed by protest due to being the illegitimate child of a man who was not an Indian and a woman who was an Indian. |

| 6(1)(a.2) | Amending the status of children born female September 4, 1951 and April 16, 1985 to Indian men outside of legal marriage. |

| 6(1)(a.3) | Entitlement for descendants of 6(1)(a.1) and 6(1)(a.2) and they were born before April 17, 1985, whether or not their parents were married to each other at the time of the birth, or they were born after April 16, 1985 and their parents were married to each other at any time before April 17, 1985. |

| 6(1)(b) | Entitlement for individuals who are members of a group declared to be a First Nation band after April 17, 1985. |

| 6(1)(d) | Reinstatement for an individual who was enfranchised by application prior to April 17, 1985. |

| 6(1)(e) | Reinstatement for an individual that was enfranchised prior to September 4, 1951 for reasons of living abroad for 5+ years without the consent of the Superintendent General or becoming ministers, doctors, lawyers ("professionals" – only until 1920). |

| 6(1)(f) | Entitlement for children with both parents entitled to registration. |

| 6(2) | Entitlement for children when only one parent is entitled to registration under 6(1) and the other parent isn't entitled to registration. |

Annex D—First Nations Bands Represented at Broader Reform Events

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on January 30, 2020, in Whitehorse, Yukon

- Council of Yukon First Nations

- Carcross/Tagish First Nation

- Champagne and Aishihik First Nations

- First Nation of Na-cho Nyak Dun

- Kluane First Nation

- Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation

- Nisga'a Village of Gitwinksihlkw

- shishalh Nation Ta'an Kwäch'än Council

- Teslin Tlingit Council

- Tr'ondëk Hwëch'in First Nation

- Tsawwassen First Nation

- Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation

- Westbank First Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 3, 2020 in Kamloops, BC

- ?akisq'nuk First Nation

- Adams Lake

- Sekw'el'was First Nation

- C'eletkwmx of Nlaka'pamux First Nations

- Cook's Ferry of Nlaka'pamux First Nations

- High Bar First Nation

- Neskonlith

- Nooaitch

- Sqilxw/Okanagan

- Shackan of Nlaka'pamux First Nations

- Secwepemc

- Simpcw First Nation

- Splatsin

- Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc

- Upper Nicola of Syilx

- Upper Similkameen

- Pellt'iq't First Nation

- Xaxli'p

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 6, 2020 in Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Berens River

- Black River First Nation

- Brokenhead Ojibway Nation

- Hollow Water

- Ochekwi-Sipi

- Lake Manitoba

- Little Saskatchewan

- Peguis

- Pinaymootang First Nation

- Red Sucker Lake

- Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation Government

- Poplar River First Nation

- St. Theresa Point

- Wasagamack First Nation

- York Factory First Nation

- Anishinaabe Agowidiiwinan Secretariat Inc.

- Southern Chiefs Organization Inc.

- Peepeekisis Cree Nation

- Interlake Reserves Tribal Council

- Manto Sipi Cree Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 7, 2020 in Winnipeg, Manitoba

- Barren Lands

- Dakota Tipi

- Fox Lake Cree Nation

- Gambler First Nation

- Manto Sipi Cree Nation

- Bunibonibee Cree Nation

- Pine Creek

- Wipazoka Wakpa

- Skownan First Nation

- Tataskweyak Cree Nation

- War Lake First Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 7, 2020 in Terrace, BC

- Secretariat of the Haida Nation

- Gitanyow

- Sik-e-dakh

- Haisla Nation

- Iskut

- Kitsumkalum

- Lax-kw'alaams First Nation

- Metlakatla First Nation

- Skidegate

- Tahltan

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 10, 2020 in The Pas, MB

- Pimicikamak Cree Nation

- Marcel Colomb First Nation

- Mathias Colomb Cree Nation

- Misipawistik Cree Nation

- Opaskwayak Cree Nation

- Sapotaweyak Cree Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 10, 2020 in Prince George, BC

- Tŝi del del First Nation

- Esk'etemc

- Fort Nelson First Nation

- Lheidli T'enneh

- McLeod Lake of Tse'Khene Nation

- Nadleh Whut'en

- Nak'azdli Whut'en

- Nazko First Nation

- Northern Shuswap Tribal Council Society

- Saik'uz First Nation

- Saulteau First Nations

- Takla Lake First Nation

- Tl'azt'en Nation

- Treaty 8 Tribal Association

- Tsilhqot'in National Government

- West Moberly First Nations

- Wet'suwet'en First Nation

- T'exelcemc

- Xeni Gwet'in First Nations Government

- Yunesit'in Government

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 12, 2020 in Nanaimo, BC

- Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council

- Wei Wai Kum First Nation

- Wei Wai Kai Nation

- Ts'uubaa-asatx Nation

- Gwa'Sala-Nakwaxda'xw Nations

- Hesquiaht

- Mowachaht/Muchalaht

- 'Namgis First Nation

- Snaw-naw-as First Nation

- Pacheedaht First Nation

- Qualicum First Nation

- Quatsino

- Tseshaht First Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 14, 2020 in Chilliwack, BC

- Chawathil First Nation

- Nlakapamux Nation Tribal Council

- T'eqt"aqtn'mux

- Lower Similkameen

- Lytton

- Osoyoos

- Penticton

- Seabird Island

- Skuppah

- Skwah

- Spuzzum

- Sts'ailes

- Sumas First Nation

- Tzeachten First Nation

- Yale First Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 14, 2020 in Ottawa, ON

- Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council

- Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation

- Beausoleil First Nation

- Chippewas of Rama First Nation

- Conseil de la Nation Anishnabe de Lac Simon

- Cree Nation of Mistissini

- Cree Nation of Nemaska

- Curve Lake

- Hiawatha First Nation

- Magnetawan

- Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation

- Mohawks of Kahnawá:ke

- Mohawks of Kanesatake

- Six Nations of the Grand River

- Ogemawahj Tribal Council

- Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation

- Première nation de Whapmagoostui

- Cree Nation of Waskaganish

- Timiskaming First Nation

- Cree Nation of Waswanipi

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 18, 2020 in Sudbury, ON

- Chapleau Cree First Nation

- Dokis First Nation

- Ketegaunseebee

- Matachewan

- M'Chigeeng First Nation

- Michipicoten

- Missanabie Cree

- Mississauga

- Moose Deer Point

- Nipissing First Nation

- Sagamok Anishnawbek

- Serpent River

- Shawanaga First Nation

- Taykwa Tagamou Nation

- Thessalon

- Wikiikwemkoong Unceded Territory

- Wikwemikong

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 20, 2020 in London, ON

- Aamjiwnaang

- Beausoleil First Nation

- Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point

- Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

- Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

- Mississaugas of the Credit

- Munsee-Delaware Nation

- Onyota'a:ka First Nations

- Six Nations of the Grand River

- Southern First Nations Secretariat

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 24, 2020 in Saskatoon, SK

- Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation

- Moosomin

- Mosquito Grizzly Bear's Head Lean Man First Nations of Assiniboine First Nation

- Muskeg Lake Cree Nation #102

- One Arrow First Nation

- Onion Lake Cree Nation

- Red Pheasant Cree Nation

- Sweetgrass

- Sikip Sakahikan

- Whitecap Dakota First Nation

- Witchekan Lake

- Yellow Quill

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 25, 2020 in Vancouver, BC

- Xa-xtsa First Nation

- Esk'etemc

- Kitasoo/Xaixais First Nation

- Kwantlen First Nation

- Kwikwetlem First Nation

- Lil'wat Nation

- Samahquam

- Songhees Nation

- Tsleil-Waututh Nation

- T'Sou-ke First Nation

- Yale First Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on February 28, 2020 in Regina, SK

- Cote First Nation

- Cowessess

- Fishing Lake First Nation

- George Gordon First Nation

- Kahkewistahaw

- Kawacatoose

- Muscowpetung Saulteaux Nation

- Okanese

- Pasqua First Nation #79

- Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation

- Star Blanket Cree Nation

- The Key First Nation

- TOUCHWOOD AGENCY TRIBAL COUNCIL

- YORKTON TRIBAL ADMINISTRATION

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on March 9, 2020 in Kenora, BC

- Anishinabe of Wauzhushk Onigum

- Mitaanjigamiing First Nation

- Naicatchewenin

- Niisaachewan Anishinaabe Nation

- Northwest Angle 33 First Nation

- Ojibways of Onigaming First Nation

- PWI-DI-GOO-ZING NE-YAA-ZHING ADVISORY SERVICES

- Wabaseemoong Independent Nations

- Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on March 10, 2020 in Halifax, NS

- Miawpukek

- Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq

- Annapolis Valley

- Eskasoni Mi'Kmaw Nation

- Membertou

- Millbrook

- Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation

- Potlotek First Nation

- SIPEKNE'KATIK

- Wagmatcook

Attendees at Broader Reform Event on March 12, 2020 in Moncton, NB

- Abegweit First Nation

- Elsipogtog First Nation

- Esgenoopetitj First Nation

- Fort Folly

- Indian Island

- Lennox Island

- Madawaska Maliseet First Nation

- Metepenagiag Mi'kmaq Nation

- Oromocto First Nation

- Neqotkuk

- Woodstock

Annex E—Bilateral First Nations Participants

British Columbia

- Cowichan Tribes

- Homalco First Nation

- Musqueam Indian Band

- Okanagan Nation Alliance / Syilx Nation

- Tseshaht First Nation

- Wei Wai Ka First Nation

Ontario

- Fort William First Nation

- Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation

- Moose Deer Point

Annex F—First Nations Participants at Departmental Training

Alberta

- Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

- Fort McKay First Nation

- Loon River First Nation

- Lubicon Lake Nation

- Piikani First Nation

- Tsuu T'ina Nation

British Columbia

- Ahousaht First Nation

- Akisqnuk First Nation

- Aqam First Nation

- Ashcroft Band

- Binche Whut'en First Nation

- Bonaparte Band

- Boston Bar First Nation

- Canim Lake Band

- Chawathil First Nation

- Coldwater Indian Band

- Cowichan Tribes

- Dzawada'enuxw First Nation (Tsawataineuk)

- Ditidaht First Nation

- Esdilagh First Nation

- Esk'etemc First Nation

- Fort Nelson Nation

- Gitga'at First Nation (Hartley Bay)

- Gitxaala Nation

- Gitxsan Government Commission

- Gwanak Nations

- Haisla National Council

- Heiltsuk First Nation

- High Bar First Nation

- Homalco First Nation

- Huu-ay-aht First Nations

- Kanaka Bar Band

- Kispiox Band

- Kitasoo Band Council

- Kwadacha Nation

- Kwikwasut'inuxw Haxwa'mis First Nation

- Kwikwetlem First Nation

- Lax Band

- Lheidli T'enneh First Nation

- Lhoosk'uz Dene Nation (Kluskus)

- Lil'wat Nation (Mount Currie)

- Little Shuswap Lake Band

- Lower Nicola Indian Band

- Lower Similkameen Indian Band

- Malahat Nation

- Mamalilikulla First Nation

- Metlakatla First Nation

- Musqueam Indian Band

- Nadleh Whut'en First Nation

- Nak'azdli Whut'en First Nation

- Namgis First Nation

- Nisga'a Village of Gingolx

- Nooaitch Indian Band

- Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council

- Nuxalk Nation

- Northern Shuswap Tribal Council

- Okanagan Nation Alliance / Syilx Nation

- Old Massett Village Council

- Osoyoos Indian Band

- Penticton Indian Band

- Qualicum First Nation

- Saulteau First Nation

- Shackan Indian Band

- Shuswap Band

- Simpcw First Nation

- Skeetchestn Band

- Skidegate

- Skwah First Nation

- Snuneymuxw First Nation

- Splatsin Indian Band

- Spuzzum First Nation

- Squamish Nation

- Sts'ailes Nation (Chehalis Indian Band)

- Stz'uminus First Nation

- Tahltan First Nation

- Takla First Nation

- Tla'amin Nation

- Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation

- Tlowitsis Tribe

- Tobacco Plains Indian Band

- Toosey Band (Tl'esqox First Nation)

- Treaty 8 Tribal Association

- Tsartlip First Nation

- Tseshaht First Nation

- Tsilhqotin Nation

- Ts'kw'aylaxw First Nation

- Tsleil-Waututh Nation (Burrard)

- T'Sou-ke First Nation

- Ucluelet First Nation

- Upper Similkameen Indian Band

- We Wai Kai Nation

- Wei Wai Kum First Nation (Campbell River Indian Band)

- West Moberly First Nation

- Westbank First Nation

- Witset First Nation

- Xaxli'p First Nation

- Yale First Nation

- Yunesit'in Government

Ontario

- Alderville First Nation

- Atikameksheng Anishnawbek

- Aundeck Omni Kaning First Nation

- Chippewas of Rama First Nation

- Deer Lake First Nation

- Fort William First Nation

- Hiawatha First Nation

- Moose Deer Point First Nation

- Saugeen First Nation

- Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation

- Wunnumin Lake First Nation

Yukon

- Carcross/Tagish First Nation

- Champagne/Aishihik First Nation

- First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun

- Liard First Nation

- Selkirk First Nation

- Trʼondëk Hwëchʼin First Nation